Understanding inflation, its real causes, its link to money, debt, and economic policy, and why it acts as a silent tax on savings.

Inflation is often presented as a simple rise in prices. This definition, while technically correct, remains superficial. It describes a visible consequence, but not the underlying mechanism. In reality, inflation is a monetary, economic, and political phenomenon deeply embedded in the functioning of modern economies.

It influences far more than the cost of living. It shapes the value of savings, wage dynamics, public policy, investment decisions, and the distribution of wealth. Yet it remains poorly understood, often reduced to a monthly figure published by statistical authorities.

Understanding inflation is not only about understanding why prices rise. It is about understanding why money gradually loses its value.

Inflation begins in the monetary system, not in prices.

Prices do not rise spontaneously. They respond to a change in the balance between the amount of money in circulation and the quantity of goods and services available in the economy.

When the money supply grows faster than real production, each monetary unit represents a smaller share of the whole. Prices then adjust upward to reflect this new reality. This process is gradual, often invisible in the short term, but cumulative over time.

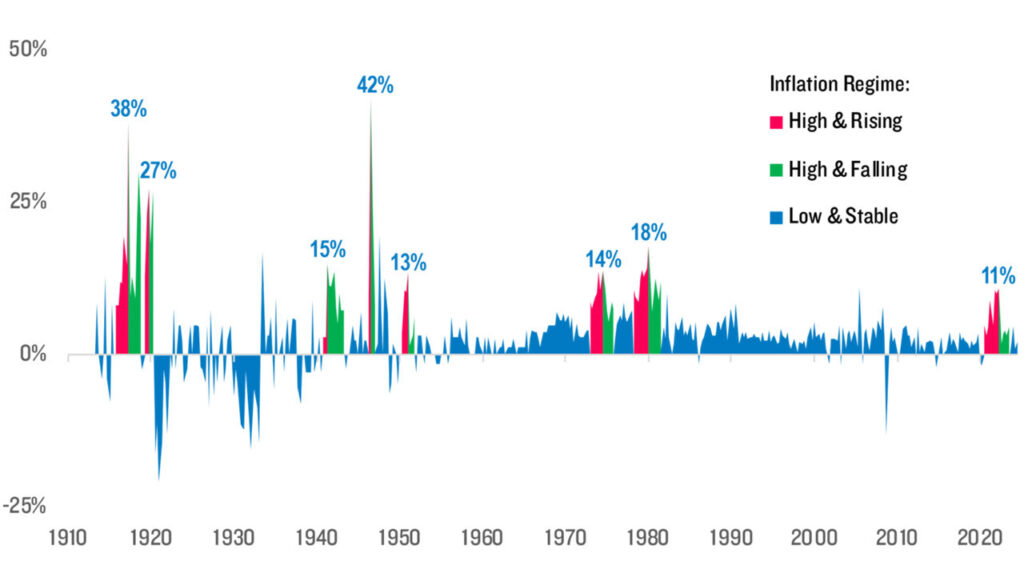

Historically, major inflationary periods have almost always been preceded by excessive monetary expansion. This relationship has been documented for centuries and confirmed by numerous contemporary analyses, notably those of the International Monetary Fund and the Bank for International Settlements.

Thus, inflation should not be understood as a problem caused by merchants or supply chains, but as a logical consequence of monetary choices.

Why do governments tolerate, and sometimes encourage, inflation?

In an ideal system, perfect price stability would be desirable. In reality, inflation plays a functional role in highly indebted economies.

Modern states finance a large portion of their spending through borrowing. When debt becomes too large, reducing its real value becomes a central concern. Inflation allows precisely that. It acts as a mechanism for the gradual devaluation of debt, without formal restructuring and without explicit political decisions.

This is why most central banks, including the Federal Reserve, target a moderate level of inflation rather than absolute price stability. Low but persistent inflation facilitates credit management and eases the real burden of public debt.

Inflation thus becomes a discreet tool of macroeconomic management.

Official inflation and experienced inflation: a structural gap

Inflation is generally measured using statistical indices such as the Consumer Price Index. These tools are useful for tracking overall trends, but they have significant limitations.

The baskets of goods used are standardized and do not necessarily reflect the actual structure of household spending. Housing, energy, education, or healthcare, which account for a growing share of budgets, often rise faster than the overall index.

This gap explains why many households experience inflation as being higher than what is officially reported. Experienced inflation is subjective, but it is often closer to everyday reality than statistical averages.

Inflation and wages: an asymmetric relationship

Contrary to a common belief, wages are not the structural cause of inflation. They are generally a delayed consequence of it.

When inflation takes hold, wages rise with a lag, following negotiations, contractual adjustments, or social pressures. This delay leads to a temporary, and sometimes lasting, loss of purchasing power for workers.

Inflation thus acts as a silent transfer of wealth, penalizing those whose incomes adjust slowly and favouring holders of assets capable of appreciating over time.

Interest rates, debt, and the central bank dilemma

Interest rates are the primary tool used to fight inflation. By raising them, central banks slow credit, consumption, and investment.

But in a high-debt environment, this mechanism becomes fragile. Rates that are too high increase the cost of servicing debt and weaken governments, businesses, and households. Rates that are too low sustain inflation and encourage borrowing.

This structural dilemma explains why inflation is rarely eradicated. It is managed and contained, but rarely eliminated in a lasting way.

Inflation and savings: invisible erosion

One of the most powerful effects of inflation is its impact on uninvested savings.

Money held as cash or placed in low-yield instruments gradually loses its real value. This erosion is slow but cumulative. Over ten or twenty years, it can represent a massive loss of purchasing power.

This is why inflation is often described as an invisible tax. It operates without a vote, without a specific law, but with formidable effectiveness.

Inflation and real assets: an imperfect but necessary response

Not all assets respond to inflation in the same way. Real assets, such as real estate, commodities, or gold, have historically been more resilient to monetary devaluation. Read my article on gold.

Gold, in particular, acts as a monetary constant. It does not protect against month-to-month inflation, but against the long-term loss of currency value. This is why it is held by central banks and integrated into certain wealth management strategies.

Why inflation has become structural

Contemporary inflation is no longer driven solely by traditional economic cycles. It is fuelled by lasting structural factors: demographic aging, industrial reshoring, geopolitical tensions, the energy transition, and high levels of debt.

These elements place constant pressure on costs and make a sustained return to very low inflation unlikely. Inflation thus becomes a permanent parameter of the economic system.

Understanding inflation to adapt more effectively

Inflation is not fought through inaction. It is understood, then managed.

Understanding its mechanisms makes it possible to adapt savings, investments, and financial decisions. The goal is not to predict every monthly fluctuation, but to build a strategy capable of preserving purchasing power over the long term.

In a world where money slowly but continuously loses value, understanding inflation becomes an essential skill.

Because it reduces the real value of money relative to goods and services.

In a system based on credit and debt, moderate inflation is structural.

By avoiding overexposure to cash and incorporating assets capable of preserving long-term value.

One Comment